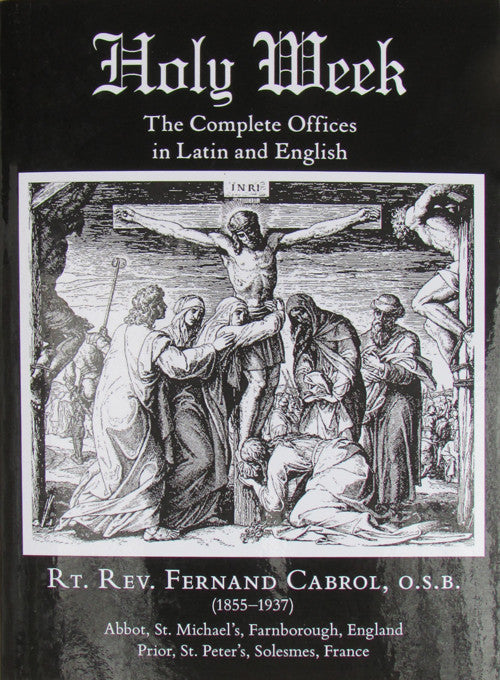

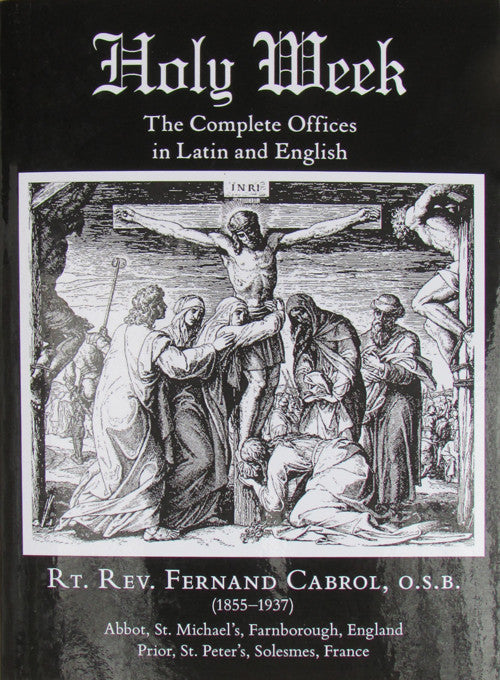

Books for Lent

$25.95 – $36.95

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Sale!

Et Reliqua

Sermons and Reflections from the Deanery

Support our apostolate

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

“The Liturgy, considered as a whole, is the collection of symbols, chants and acts by means of which the Church expresses and manifests its religion towards God.”

IN THE OLD TESTAMENT, God Himself, so to speak, is the liturgist: He specifies the most minute details of the worship which the faithful had to render to Him. The importance attached to a form of worship which was but the shadow of that sublime worship in the New Testament which Christ the High Priest wanted His Church to continue until the end of the world. In the Liturgy of the Catholic Church, everything is important, everything is sublime, down to the tiniest details, a truth which moved St. Teresa of Avila to say: “I would give my life for the smallest ceremony of Holy Church.”

The reader, therefore, should not be surprised at the importance we will attach to the rubrics of the Liturgy, and the close attention we will pay to the “reforms” which preceded the Second Vatican Council.

In any case, the Church’s enemies were all too well aware of the importance of the Liturgy — heretics corrupted the Liturgy in order to attack the Faith itself. Such was the case with the ancient Christological heresies, then with Lutheranism and Anglicanism in the 16th century, then with the Illuminist and Jansenist reforms in the 18th century, and finally with Vatican II, beginning with its Constitution on the Liturgy and culminating in the Novus Ordo Missae.

The liturgical “reform” desired by Vatican II and realized in the post-Conciliar period is nothing short of a revolution. No revolution has ever come about spontaneously. It always results from prolonged attacks, slow concessions, and a gradual giving way. The purpose of this article is to show the reader how the liturgical revolution came about, with special reference to the pre-Conciliar changes in 1955 and 1960.

Msgr. Klaus Gamber, a German liturgist, pointed out that the liturgical debacle pre-dates Vatican II. If, he said, “a radical break with tradition has been completed in our days with the introduction of the Novus Ordo and the new liturgical books, it is our duty to ask ourselves where its roots are. It should be obvious to anyone with common sense that these roots are not to be looked for exclusively in the Second Vatican Council. The Constitution on the Liturgy of December 4, 1963 represents the temporal conclusion of an evolution whose multiple and not all homogenous causes go back into the distant past.”

According to Mgr Gamber. “The flowering of church life in the Baroque era (the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent) was stricken towards the end of the eighteenth century, with the blight of Illuminism. People were dissatisfied with the traditional liturgy, because they felt it did not correspond with the concrete problems of the times.” Rationalist Illuminism found the ground already prepared by the Jansenist heresy, which, like Protestantism, opposed the traditional Roman Liturgy.

Emperor Joseph II, the Gallican bishops of France, and of Tuscany in Italy, meeting together for the Synod of Pistoia, carried out reforms and liturgical experiments “which resemble to an amazing extent the present reforms; they are just as strongly orientated towards Man and social problems.”…”We can say, therefore, that the deepest roots of the present liturgical desolation are grounded in Illuminism.”

The aversion for tradition, the frenzy for novelty and reforms, the gradual replacement of Latin by the vernacular, and of ecclesiastical and patristic texts by Scripture alone, the diminution of the cult of the Blessed Virgin and the saints, the suppression of liturgical symbolism and mystery, and finally the shortening of the Liturgy, it judged to be excessively and uselessly long and repetitive — we find all these elements of the Jansenist liturgical reforms in the present reforms, and see them reflected especially in the reforms of John XXIII. In the most serious cases the Church condemned the innovators: thus, Clement IX condemned the Ritual of the Diocese of Alet in 1668, Clement XI condemned the Oratorian Pasquier Quesnel (1634-1719) in 1713, Pius VI condemned the Synod of Pistoia and Bishop Scipio de’ Ricci in his bull Auctorem Fidei in 1794.

“A reaction to the llluminist plague,” says Mgr. Gamber. “is represented by the restoration of the nineteenth century. There arose at this time the great French Benedictine abbey of Solesmes, and the German Congregation of Beuron.” Dom Prosper Gueranger (1805-1875), Abbot of Solesmes, restored the old Latin liturgy in France.

His work led to a movement, later called the “Liturgical Movement,” which sought to defend the traditional liturgy of the Church, and to make it loved. This movement greatly benefited the Church up to and throughout the reign of St. Pius X, who restored Gregorian Chant to its position of honor and created an admirable balance between the Temporal Cycle (feasts of Our Lord, Sundays, and ferias) and the Sanctoral Cycle (feasts of the saints).

After St. Pius X, little by little, the so called “Liturgical Movement” strayed from its original path, and came full circle to embrace the theories which it had been founded to combat. All the ideas of the anti-liturgical heresy — as Dom Guéranger called the liturgical theories of the 18th century — were now taken up again in the 1920s and 30s by liturgists like Dom Lambert Beauduin (1873-1960) in Belgium and France, and by Dom Pius Parsch and Romano Guardini in Austria and Germany.

The “reformers” of the 1930s and 1940s introduced the “Dialogue Mass,” because of their “excessive emphasis on the active participation of the faithful in the liturgical functions.” In some cases — in scout camps, and other youth and student organizations — the innovators succeeded in introducing Mass in the vernacular, the celebration of Mass on a table facing the people, and even concelebration. Among the young priests who took a delight in liturgical experiments in Rome in 1933 was the chaplain of the Catholic youth movement, a certain Father Giovanni Battista Montini.

In Belgium, Dom Beauduin gave the Liturgical Movement an ecumenical purpose, theorizing that the Anglican Church could be “united [to the Catholic Church] but not absorbed.” He also founded a “Monastery for Union” with the Eastern Orthodox Churches, which resulted in many of his monks “converting” to the eastern schism. Rome intervened: the Encyclical against the Ecumenical Movement, Mortalium Animos (1928) resulted in Dom Beauduin being discreetly recalled, a temporary diversion. The great protector of Beauduin was Cardinal Mercier, founder of “Catholic” ecumenism, and described by the anti-modernists of the time as the “friend of all the betrayers of the Church.”

In the 1940s liturgical saboteurs had already obtained the support of a large part of the hierarchy, especially in France (through the CPL — Center for Pastoral Liturgy) and in Germany.

On January 18, 1943, the most serious attack against the Liturgical Movement was launched by an eloquent and outspoken member of the German hierarchy, the Archbishop of Freiburg, Conrad Grober. In a long letter addressed to his fellow bishops, Grober gathered together seventeen points expressing his criticisms of the Liturgical Movement. He criticized the theology of the charismatics, the Schoenstatt movement, but above all the Liturgical Movement, involving implicitly also Theodor Cardinal Innitzer of Vienna.

Few people know that Fr. Karl Rahner, SJ, who then lived in Vienna, wrote a response to Grober. We shall meet Karl Rahner again as the German hierarchy’s conciliar “expert” at the Second Vatican Council, together with Hans Küng and Schillebeeckx.

The dispute ended up in Rome. In 1947 Pius Xll’s Encyclical on the liturgy, Mediator Dei, ratified the condemnation of the deviating Liturgical Movement.

Pius XII “strongly espoused Catholic doctrine, but the sense of this encyclical was distorted in the commentaries made on it by the innovators and Pius XII, even though he remembered the principles, did not have the courage to take effective measures against those responsible; he should have suppressed the French CPL and prohibited a good number of publications. But these measures would have resulted in an open conflict with the French hierarchy”.

Having seen the weakness of Rome, the reformers saw that they could move forward: from experiments they now passed to official Roman reforms.

Pius XII underestimated the seriousness of the liturgical problem: “It produces in us a strange impression,” he wrote to Bishop Grober, “if, almost from outside the world and time, the liturgical question has been presented as the problem of the moment.”

The reformers thus hoped to bring their Trojan Horse into the Church, through the almost unguarded gate of the Liturgy, profiting from the scant attention of Pope Pius XII paid to the matter, and helped by persons very close to the Pontiff, such as his own confessor Agostino Bea, future cardinal and “super-ecumenist.”

The following testimony of Annibale Bugnini is enlightening:

“The Commission (for the reform of the Liturgy instituted in 1948) enjoyed the full confidence of the Pope, who was kept informed by Mgr. Montini, and even more so, weekly, by Fr. Bea, the confessor of Pius Xll. Thanks to this intermediary, we could arrive at remarkable results, even during the periods when the Pope’s illness prevented anyone else getting near him.”

Fr. Bea was involved with Pius XII’s first liturgical reform, the new liturgical translation of the Psalms, which replaced that of St. Jerome’s Vulgate, so disliked by the protestants, since it was the official translation of the Holy Scripture in the Church, and declared to be authentic by the Council of Trent. (Motu proprio, In cotidianis precibus, of March 24, 1945.) The use of the New Psalter was optional, and enjoyed little success.

After this reform, came others which would last longer and be more serious:

The following section will discuss the reform of Holy Week. Meanwhile, what of the rubrical reforms made in 1956 by Pius XII ? They they were an important stage in the liturgical reforms, as we will see when we examine the reforms of John XXIII. For now it is enough to say that the reforms tended to shorten the Divine Office and diminish the cult of the saints. All the feasts of semidouble and simple ranks became simple commemorations; in Lent and Passiontide one could choose between the office of a saint and that of the feria; the number of vigils was diminished and octaves were reduced to three. The Pater, Ave and Credo recited at the beginning of each liturgical hour were suppressed; even the final antiphon to Our Lady was taken away, except at Compline. The Creed of St. Athanasius was suppressed except for once a year.

In his book, Father Bonneterre admits that the reforms at the end of the pontificate of Pius XII are “the first stages of the self-destruction of the Roman Liturgy.” Nevertheless, he defends them because of the “holiness” of the pope who promulgated them.

“Pius XII,” he writes, “undertook these reforms with complete purity of intention, reforms which were rendered necessary by the need of souls. He did not realize — he could not realize — that he was shaking discipline and the liturgy in one of the most crucial periods of the Church’s history; above all, he did not realize that he was putting into practice the program of the straying liturgical movement.”

Jean Crete comments on this:

“Fr. Bonneterre recognizes that this decree signaled the beginning of the subversion of the liturgy, and yet seeks to excuse Pius XIl on the grounds that at the time no one, except those who were party to the subversion, was able to realize what was going on. I can, on the contrary, give a categorical testimony on this point. I realized very well that this decree was just the beginning of a total subversion of the liturgy, and I was not the only one. All the true liturgists, all the priests who were attached to tradition, were dismayed.

“The Sacred Congregation of Rites was not favorable toward this decree, the work of a special commission. When, five weeks later, Pius XII announced the feast of St. Joseph the Worker (which caused the ancient feast of Ss. Philip and James to be transferred, and which replaced the Solemnity of St Joseph, Patron of the Church), there was open opposition to it.

“For more than a year the Sacred Congregation of Rites refused to compose the office and Mass for the new feast. Many interventions of the pope were necessary before the Congregation of Rites agreed, against their will, to publish the office in 1956 — an office so badly composed that one might suspect it had been deliberately sabotaged. And it was only in 1960 that the melodies of the Mass and office were composed — melodies based on models of the worst taste.

“We relate this little-known episode to give an idea of the violence of the reaction to the first liturgical reforms of Pius XII”.

“The liturgical renewal has clearly demonstrated that the formulae of the Roman Missal have to be revised and enriched. The renewal was begun by the same Pius XII with the restoration of the Easter Vigil and the Order of Holy Week, which constituted tile first stage of the adaptation of the Roman Missal to the needs of our times.”

These are the very words of Paul VI when he promulgated the New Mass on April 3, 1969. This clearly demonstrates how the pre-Conciliar and post-Conciliar changes are related. Likewise, Msgr. Gamber wrote that

“The first Pontiff to bring a real and proper change to the traditional missal was Pius XII, with the introduction of the new liturgy of Holy Week. To move the ceremony of Holy Saturday to the night before Easter would have been possible without any great modification. But then along came John XXIII with the new ordering of the rubrics. “Even on these occasions, however, the Canon of the Mass remained intact. [Also John XXIII introduced the name of St. Joseph into the Canon during the council, violating the tradition that only the names of martyrs be mentioned in the Canon.] It was not even slightly altered. But after these precedents, it is true, the doors were opened to a radically new ordering of the Roman Liturgy.”

The decree, Maxima Redemptionis, which introduced the new rite in 1955, speaks exclusively of changing the times of the ceremonies of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, to make it easier for the faithful to assist at the sacred rites, now transferred after centuries to the evenings those days.

But no passage in the decree makes the slightest mention of the drastic changes in the texts and ceremonies themselves. In fact, the new rite of Holy Week was a nothing but a trial balloon for post-Conciliar reform which would follow. The modernist Dominican Fr. Chenu testifies to this:

“Fr. Duploye followed all this with passionate lucidity. I remember that he said to me one day, much later on. ‘If we succeed in restoring the Easter Vigil to its original value, the liturgical movement will have won; I give myself ten years to achieve this.’ Ten years later it was a fait accompli.”

In fact, the new rite of Holy Week, is an alien body introduced into the heart of the Traditional Missal. It is based on principles which occur in Paul VI’s 1965 reforms.

Here are some examples:

Here is a partial list of other innovations introduced by the new Holy Week:

This brief examination of the reform of Holy Week should allow the reader to realize how the “experts” who would come up with the New Mass fourteen years later had used and taken advantage of the 1955 Holy Week rites to test their revolutionary experiments before applying them to the whole liturgy.

Pius XII succeeded by John XXIII. Angelo Roncalli. Throughout his ecclesiastical career, Roncalli was involved in affairs that place his orthodoxy under a cloud. Here are a few facts:

As professor at the seminary of Bergamo, Roncalli was investigated for following the theories of Msgr. Duchesne, which were forbidden under Saint Pius X in all Italian seminaries. Msgr Duchesne’s work, Histoire Ancienne de l’Eglise, ended up on the Index.

While papal nuncio to Paris, Roncalli revealed his adhesion to the teachings of Sillon, a movement condemned by St. Pius X. In a letter to the widow of Marc Sagnier, the founder of the condemned movement, he wrote: The powerful fascination of his [Sagnier’s] words, his spirit, had enchanted me; and from my early years as a priest, I maintained a vivid memory of his personality, his political and social activity.”

Named as Patriarch of Venice, Msgr.Roncalli gave a public blessing to the socialists meeting there for their party convention. As John XXIII, he made Msgr. Montini a cardinal and called the Second Vatican Council. He also wrote the Encyclical Pacem in Terris. The Encyclical uses a deliberately ambiguous phrase, which foreshadows the same false religious liberty the Council would later proclaim.

John XXIII’s attitude in matters liturgical, then, comes as no surprise. Dom Lambert Beauduin, quasi-founder of the modernist Liturgical Movement, was a friend of Roncalli from 1924 onwards. At the death of Pius XII, Beauduin remarked: “If they elect Roncalli, everything will be saved; he would be capable of calling a council and consecrating ecumenism…”‘

On July 25, 1960, John XXIII published the Motu Proprio Rubricarum Instructum. He had already decided to call Vatican II and to proceed with changing Canon Law. John XXIII incorporates the rubrical innovations of 1955–1956 into this Motu Proprio and makes them still worse. “We have reached the decision,” he writes, “that the fundamental principles concerning the liturgical reform must be presented to the Fathers of the future Council, but that the reform of the rubrics of the Breviary and Roman Missal must not be delayed any longer.”

In this framework, so far from being orthodox, with such dubious authors, in a climate which was already “Conciliar,” the Breviary and Missal of John XXIII were born. They formed a “Liturgy of transition” destined to last — as it in fact did last — for three or four years. It is a transition between the Catholic liturgy consecrated at the Council of Trent and that heterodox liturgy begun at Vatican II.

We have already seen how the great Dom Guéranger defined as “liturgical heresy” the collection of false liturgical principles of the 18th century inspired by Illuminism and Jansenism. I should like to demonstrate in this section the resemblance between these innovations and those of John XXIII.

Since John XXIII’s innovations touched the Breviary as well as the Missal, I will provide some information on his changes in the Breviary also. Lay readers may be unfamiliar with some of the terms concerning the Breviary, but I have included as much as possible to provide the “flavor” and scope of the innovations.

John XXIII, going well beyond the well-balanced reform of St. Pius X, fulfills almost to the letter the ideal of the Janenist heretics: only nine feasts of the saints can take precedence over the Sunday (two feasts of St. Joseph, three feasts of Our Lady, St. John the Baptist, Saints Peter and Paul, St. Michael, and All Saints). By contrast, the calendar of St. Pius X included 32 feasts which took precedence, many of which were former holydays of obligation. What is worse, John XXIII abolished even the commemoration of the saints on Sunday.

John XXIII totally suppressed ten feasts from the calendar (eleven in Italy with the feast of Our Lady of Loreto), reduced 29 feasts of simple rank and nine of more elevated rank to mere commemorations, thus causing the ferial office to take precedence. He suppressed almost all the octaves and vigils, and replaced another 24 saints’ days with the ferial office. Finally, with the new rules for Lent, the feasts of another nine saints, officially in the calendar, are never celebrated. In sum, the reform of John XXIII purged about 81 or 82 feasts of saints, sacrificing them to “Calvinist principles.”

Dom Gueranger also notes that the Jansenists suppressed the feasts of the saints in Lent. John XXIII did the same, keeping only the feasts of first and second class. Since they always fall during Lent, the feasts of St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Gregory the Great. St. Benedict, St. Patrick, and St. Gabriel the Archangel would never be celebrated.

We have seen that the reform of 1960 suppresses two out of three lessons of the Second Nocturn of Matins, in which the lives of the saints are read. But this was not enough. As we mentioned, eleven feasts were totally suppressed by the preconciliar rationalists. For example, St. Vitus, the Invention of the Holy Cross, St. John before the Latin Gate, the Apparition of St. Michael on Mt. Gargano, St. Anacletus, St. Peter in Chains, the Finding of St. Stephen, Our Lady of Loreto (“A flying house! How can we believe that in the twentieth century!”); among the votive feasts, St. Philomena (the Cure of Ars was so “stupid” to have believed in her).

Other saints were were eliminated more discreetly: Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Our Lady of Ransom, St. George, St. Alexis, St. Eustace, the Stigmata of St. Francis — these all remain, but only as a commemoration on a ferial day.

Two popes are also removed, seemingly without reason: St. Sylvester (was he too triumphalistic?) and St. Leo II (the latter, perhaps, because he condemned Pope Honorius.)

We note finally a “masterwork” which touches us closely. From the prayer to Our Lady of Good Counsel, the 1960 reform removed the words which speak of the miraculous apparition of her image, if the House of Nazareth cannot fly to Loreto, how can we imagine that a picture which was in Albania can fly to Genzzano?

These three principles will be the public boast of the reform of 1955 and 1960: the long petitions in the Office called Preces disappear; so too, the commemorations, the suffrages, the Pater, Ave, and Credo, the antiphons to Our Lady, the Athanasian Creed, two-thirds of Matins, and so on.

11. Ecumenism in the Reform of John XXIII. The Jansenists hadn’t thought of this one. The reform of 1960 suppresses from the prayers of Good Friday the Latin adjective perfidis (faithless) with reference to the Jews, and the noun perfidiam (impiety) with reference to Judaism. It left the door open for John Paul II’s visit to the synagogue.

Number 181 of the 1960 Rubrics states: “The Mass against the Pagans shall be called the Mass for the Defense of the Church. The Mass to Take Away Schism shall be called the Mass for the Unity of the Church.”

These changes reveal the liberalism, pacifism, and false ecumenism of those who conceived and promulgated them.

Now this attack on dogma was already included in the Breviary of John XXIII it obliged the priest when reciting it alone to say Domine exaudi orationem meam (O Lord, hear my prayer) instead of Dominus vobiscum (The Lord be with you). The idea, “a profession of purely rational faith.” was that the Breviary was not the public prayer of the Church any more, but merely private devotional reading.

Theory is of no use to anyone, unless it is applied in practice. This article cannot conclude without a warm invitation, above all to priests. to return to the liturgy “canonized” by the Council of Trent, and to the rubrics promulgated by St. Pius X.

Msgr Gamber writes: “Many of the innovations promulgated in the last twenty-five years — beginning with the decree on the renewal of the liturgy Holy Week of February 9, 1951 [still under Pius XII] and with the new Code of rubrics of July 25, 1960, by continuous small modifications, right up to the reform of the Ordo Missae of April 3. 1969 — have been shown to be useless and dangerous to their spiritual life.”

Unfortunately, in the “traditionalist” camp, confusion reigns: one stops at 1955; another at 1965 or 1967. Archbishop Lefebvre’s followers, having first adopted the reform of 1965, returned to the 1960 rubrics of John XXIII even while permitting the introduction of earlier or later uses! There, in Germany, England, and the United States, where the Breviary of St. Pius X had been, recited, the Archbishop attempted to impose the changes of John XXIII. This was not only for legal motives, but as a matter of principle; meanwhile, the Archbishop’s followers barely tolerated the private recitation of the Breviary of St. Pius X.

We hope that this and other studies will help people understand that these changes are part of the same reform and that all of it must be rejected if all is not accepted. Only with the help of God — and clear thinking — will a true restoration of Catholic worship be possible.

The first stepping stone to the New Mass. It began with a complete overhaul of the ancient and venerable ceremonies and texts of Holy Week, introducing the altar facing the people on Palm Sunday, vernacular into the liturgy on Holy Saturday, and the abolition of the most ancient ceremony still in use, the Mass of the Presanctified on Good Friday. A few years later, most of the vigils and octaves were suppressed, as well as the First Vespers of most feasts, the Preces and many other texts of the Breviary. The author of the Pius XII reforms was Fr. Annibale Bugnini, a self-confessed freemason, who was appointed by Pius XII as Secretary to the Commission of Liturgical Reform. The only traditional group that we know of to choose their litugy based on this first stage of the Bugnini Reforms is the CMRI.

The second stepping stone was not long in coming, as John XXIII appointed Bugnini to the post of Secretary of the Pontifical Preparatory Commission on the Liturgy, signalling the approval of his fellow mason’s “progressive” approach to the liturgy. With Bugnini’s guidance, John XXIII totally suppressed ten feasts from the calendar (eleven in Italy with the feast of Our Lady of Loreto), reduced 29 feasts of simple rank and nine of more elevated rank to mere commemorations, thus causing the ferial office to take precedence. He suppressed almost all the octaves and vigils, and replaced another 24 saints’ days with the ferial office. Finally, with the new rules for Lent, the feasts of another nine saints, officially in the calendar, are never celebrated. In sum, the reform of John XXIII purged about 81 or 82 feasts of saints, sacrificing them to “Calvinist principles.” The next and most startling stage of the John XXIII reforms was to make a change to the canon of the Mass, the first since Pope Gregory the Great in the seventh century, with the introduction of the name of St. Joseph. This unleashed the more comprehensive attack on the Mass that would continue after the death of John XXIII. The so-called Missal and Breviary of 1962 are based on this short-lived stage of the liturgical reforms. This version of the new and seriously contaminated liturgy is celebrated by the Society of St. Pius X, the Fraternity of St. Peter, and most of the other traditional and indult groups today.

Despite its popularity among traditional Catholics today, it is important to note that the 1962 Missal was in force for a mere three years before replaced by Paul VI’s 1965 Missal. Now, the final onslaught of the Bugnini reforms would begin their final stages. The Prayers at the Foot of the Altar were reduced to almost nothing, the Latin reading of the Epistle and Gospel was replaced by readings in the vernacular facing the people, and the Last Gospel was suppressed altogether. Another three years later, the entire Mass came under the inspection of a liturgical commission replete with Protestants, and all references to Mass being a sacrifice were expunged from the missal. The New Mass was introduced in 1969, the work of Bugnini was done, and Paul VI rewarded him by consecrating him an archbishop.

The Guild of St. Peter ad Vincula categorically rejects all the so-called reforms of modernist and freemason Annibale Bugnini, and has adopted the mission of preserving and restoring the revered and ancient form of the liturgy in use before his first changes to the Missal and Breviary.

One of the fundamental elements of the Guild’s Rule is the exclusive use of the Traditional Rites of the Church for the celebration of Mass, the administration of the Sacraments, and the recitation (both in public and private) of the Divine Office. The Guild defines the Traditional Rites of the Church as “those prayers, rites and ceremonies used for the celebration of Mass, the administration of the Sacraments, and other liturgical rites found in liturgical books approved by the Holy See for use in the Roman Rite of the Roman Catholic Church prior to the year 1950.”

The rubrics of the Missale Romanum of St. Pius V, the Breviarium Romanum of St. Pius X, the Cæremoniale Episcoporum, and the decisions and decrees of the Sacred Congregation of Rites are followed for liturgical worship. Use of the so-called “Revised Psalter of Pius XII” is expressly forbidden to Guild members, even in private devotion. No member of the Guild shall ever, whether publicly or in private, employ the rubrics of any of the liturgical reforms instituted since the 1950s, including the revised Holy Week, or any of the other modifications authored by the liturgical reformers as stepping stones to the Novus Ordo. No dispensation shall be requested or granted in this regard for any reason.